What happens when a scuba diver resurfaces too quickly and what is this called?

A diver’s ascent speed after a dive is important to observe. If you use a dive computer this is one of the easiest ways to follow the correct ascent speed. Plus if your dive is a decompression stop dive, your dive computer will tell you when to stop and the correct duration for each stop. Then all you have to do is to control your buoyancy on your ascent.

But you may be wondering what is it called when a diver comes up too fast. When a scuba diver comes up too fast this is called a fast ascent. Fast ascents can cause nitrogen bubbles to form inside the body, which can result in mild to severe symptoms of decompression sickness or The Bends. The most severe cases of decompression sickness can result in death.

The best way to do more diving is to book yourself on a scuba diving liveaboard. You can check the latest and best deals on liveaboards using the following window:

Sorry to be so dramatic. But all you need to learn is how to ascend at the correct speed.

As an aside, in this article about where to find great white sharks, you may be as surprised as I was to discover some of the places where you find great white sharks! Place number 6 is the one that surprised me the most, but if you live in the States, you may be more surprised at places two, three and four.

What happens if and when a diver comes up too fast?

78% of air breathed is nitrogen. At depth and because of the additional pressure, this nitrogen is absorbed into your body’s tissues in greater amounts. It is these increased levels of nitrogen that need to be considered when you ascend from depth, especially if this is too fast.

As you ascend from depth the water pressure reduces. As the pressure reduces, and if it reduces too quickly, the dissolved nitrogen will form into bubbles. The pressure will only reduce too quickly if you ascend too quickly. If you ascent too quickly you will ‘fizz-up.’ This ‘fizzing-up‘ is referred to as either decompression sickness or the bends.

When a scuba diver comes ascends too quickly nitrogen bubbles form. The severity of decompression sickness and any resulting injury depends on the number of bubbles and where they form inside the body.

How to avoid a fast ascent

The best way to avoid a fast ascent is to use a dive computer. Dive computers monitor depth and pressure changes on your ascent. If the change in pressure is happening too quickly, as a result of ascending too fast, your computer will warn you with an audible beeping sound.

If you don’t have a dive computer, you should ascend at a rate which is slower than your smallest bubbles, which are the bubbles formed as you breathe out.

Pro Diver’s Tip: All dives are decompression dives. The minute you leave the surface your body is subjected to greater pressures than at the surface. Which means you will begin to absorb more nitrogen immediately. This extra absorbed nitrogen needs to time escape slowly. Which means you must therefore always ascend slowly from any dive depth. Most diving organisations refer to dives not requiring decompression stops as no-decompression dives. This is a mistake and gives a false sense of security.

How do you ascend at the correct speed from a dive?

The easiest way to control your ascent is to mange your buoyancy as you ascend using your buoyancy control device (BCD) or your drysuit. the concept is the same for both.

As you ascend from depth the air inside your buoyancy control device (or your drysuit) will expand. As it expands you become more buoyant. The more buoyant you become the faster you will ascend. To keep your ascent under control and at the correct speed you need to slowly release air from your BCD or drysuit.

You want to release enough air from your BCD or drysuit to slow your ascent to the correct speed. But not too much so you become negatively buoyant so you start to descend again. The art of controlling your buoyancy on an ascent will come with practice.

Why do they call decompression sickness the bends?

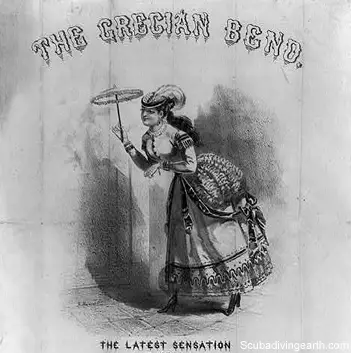

Decompression sickness was called the bends because divers who were afflicted by this disease characteristically bent forward at the hips in pain. Most people know the term ‘The Bends.’ This is the original term used for decompression sickness, which is also referred to as Caisson disease.

There is also the belief that the name ‘the bends‘ was possibly characterised from the then popular women’s fashion and dance manoeuvre known as the Grecian Bend.

See below for more of the symptoms of the bends.

Caissons were enormous compressed air boxes. These were used to build riverine piers and abutments and were first used to build the Brooklyn Bridge New York and Eads Bridge in St. Loius.

The workers who worked in these Caissons suffered from decompression sickness. Which is why decompression sickness is sometimes referred to as Caisson disease.

Can the bends be fatal?

The bends is a serious disease, which in the most serious of cases can be fatal. Other serious consequences of the bends includes paralysis or coma. This means the bends must be avoided at all costs.

How do you treat the bends?

The best and most reliable option to treat a diver with the bends is to get them to a hyperbaric chamber. In a hyperbaric chamber they are re-pressurised down to a depth at least equal to their maximum depth or deeper. They are then returned slowly to atmospheric pressure.

When a diver has had a fast ascent and when decompression sickness is likely, the diver should be put onto oxygen immediately. The oxygen administration will continue throughout their treatment. This includes when they are in the hyperbaric chamber.

What are the symptoms of the bends?

Decompression sickness produces many different symptoms. These symptoms will vary depending on the depth dived to. They will also be affected by how fast the ascent was. But also, the type and severity of a bend will vary from person to person.

The symptoms of decompression sickness depends on the level of DCS you have. The levels of DCS fall into two categories, as follows:

Type I decompression sickness (low severity) – Affects the muscles and skeletal parts of the body

Type I decompression sickness is the least severe type you can have. The main symptom of type I is pain.

- The pain usually occurs in the joints of the arms, legs or back. Often times the location of this pain may be difficult to pin down.

- The pain may start off to be mild but will usually increase over time.

- It can sometimes become quite severe pain and lead to the casualty leaning over as a result of pain in their hips.

- The pain is described as a sharp stabbing pain. It will feel like someone’s boring into your bones.

Other symptoms of Type I DCS might include:

- Loss of appetite.

- Skin rashes and itching.

- Skin mottling.

- Swollen lymph nodes.

- Extreme fatigue.

The symptoms of Type I are not in themselves life threatening, but they may precede more dangerous problems. Type I symptoms may lead to Type II symptoms.

In all cases, medical attention should be sought and oxygen be administered immediately.

Type II decompression sickness (high severity) – Neurological symptoms

Type II DCS is the more severe type of decompression sickness. At this level of decompression sickness the spinal cord is particularly vulnerable. In the worst case of Type II decompression sickness the diver can become paralysed or die.

Type II symptoms can follow on from Type I symptoms. So always be aware that just because the casualty is only suffering from mild DCS symptoms, more severe symptoms may follow.

Spinal cord decompression sickness

When the spinal cord is involved in the DCS symptoms it will have been caused by nitrogen bubbles entering the spinal column. As the bubbles expand on the spinal cord they can have a have a damaging affect.

Spinal cord decompression sickness can lead to:

- Numbness.

- Tingling like pins and needles.

- Weakness.

- Or a combination of all these feelings in the arms, legs, or both.

- The initial mild weakness or tingling can ultimately lead to irreversible paralysis. This can occur over a few hours from when the symptoms first began.

- Other symptoms of the spinal cord being affected include the inability to urinate.

- Or to the other extreme the casualty may become incontinent and have the inability to control urination or defecation.

- Back and abdomen pain are also common symptoms.

Brain affected decompression sickness

Where the symptoms of Type II DCS have affected the brain, this is caused from nitrogen bubbles forming in the brain or when bubbles have travelled through the veins to end up in the brain.

The symptoms of brain affect decompression sickness include:

- Headaches.

- Double vision.

- Confusion.

- Difficulty speaking or slurred speech.

- Loss of consciousness.

Inner ear decompression sickness

When the symptoms of decompression sickness involve the inner ear can result in:

- Loss of hearing.

- Severe vertigo.

- Ringing in the ears or tinnitus.

Inner ear decompression sickness is when nitrogen bubbles have formed in or around the inner ear.

Lung affected decompression sickness

Lung affected decompression sickness symptoms include:

- Coughing.

- Mild or severe chest pain.

- A progressively worsening difficulty in breathing. This in itself can lead to shock and death too.

Lung affected decompression sickness is caused by nitrogen gas bubbles travelling through the veins to the lungs or as a result of bubbles forming in the lungs.

How can DCS be avoided? 17 tips on how to avoid decompression sickness

1. Plan your dive and dive the plan is the best way to avoid decompression sickness

When you plan your dive make sure you stick to the plan. Especially your planned dive depth.

2. Diving within your certification level and experience will avoid any decompression problems

Build up your experience slowly and never dive beyond the depth you are certified to dive to. Wait until you have completed at least 20 dives before you move up to the next certification level.

3. Learn to control your buoyancy to control your ascent rate

Be in control of your buoyancy on your ascent so your buoyancy doesn’t get out of control. Make sure to dump air from your buoyancy control device as you ascend to control your speed of ascent.

4. Always ascending slowly from a dive will avoid any risk of decompression sickness

A fast ascent is what causes the bends. Therefore slow ascents will keep you safe. Use your dive computer to monitor your ascent rate and your buoyancy control device to regulate the speed of ascent.

5. Adhere to safety stops on every dive you do

A safety stop at 5-6 metres (16-20 feet) for three minutes is recommended for every dive, which is good safe diving practice. In this article on emergency decompression stop vs safety stop, I explain about the importance of safety stops and decompression stops.

6. Carry out decompression stops when required on decompression-stop dives

If your planned dive includes decompression stops make sure to stop at the required depth for the correct amount of time. Also make sure you do all deco-stops. Never miss a planned decompression stop.

7. Make sure you have enough air for your deco-stops when you leave for the surface

If your dive plan includes decompression stops make sure you have enough air in your dive tank when you leave the bottom.

8. Avoid yo-yo diving profiles

Yo-yo diving is when you constantly increase and decrease your depth significantly throughout the dive. This type of diving has never been recommended for safety reasons. You should always dive to the deepest part of your dive first and slowly ascend from there. Once you have ascended more than a several metres or feet you should not return to that depth again on the same dive.

9. Make sure you don’t run out of air to avoid having to make a fast ascent

Running out of air is probably one of the top causes of a fast ascent. Check your air regularly and always return to the surface with your reserve air.

10. Always dive with a buddy who should have an alternative air source

Buddy diving is taught by all international dive schools. Always dive in buddy pairs with an alternative air source in case of an emergency.

11. Check and maintain your equipment to minimise the risk of equipment failure

Equipment failure is one of the top causes of fast ascents. Make sure you have your scuba equipment serviced and checked regularly.

12. Stay hydrated when you scuba dive

Being hydrated lessens the risk of getting the bends. Always drink plenty when before your dive. Make sure to read this article about the decompression sickness risk factors.

13. Never dive drunk or with a severe hangover

You should never mix alcohol and scuba diving. Even drinking the night before and diving on a hangover could affect you. If you’ve had a heavy session the night before, make sure you re-hydrate yourself well. Or better still don’t dive until the after affects of drinking have passed.

14. Don’t fly immediately after diving

You must leave at least 24 hours between your last dive and when you fly. This avoids the risk of getting the bends on the flight.

More Reading: How long should you wait to fly after diving? (What’s safe?)

15. Get checked for a hole in the heart or a septal defect

Many scuba divers with a hole in the heart or a septal defect can be susceptible to unexpected decompression sickness. Get this checked out at your local GP or hospital.

16. Always make sure there’s oxygen on the dive boat

In the vent of a fast ascent oxygen is a must have resource for immediate administration to the casualty. Oxygen lessons the effects of decompression sickness.

17. Be cautious when planning a dive with decompression stops

If your dive includes decompression stops make sure you carry out adequate planning for these stops. Plan for the extra air consumption needed for each decompression stop. Make sure to take account of how air is consumed faster the deeper you go.

Please don’t forget to take a look at this article about where to find great white sharks, you may be as surprised as I was to discover some of the places where you find great white sharks! Place number 6 is the one that surprised me the most, but if you live in the States, you may be more surprised at places two, three and four.

I hope you enjoyed this article about what is it called when a diver comes up too fast

I’d love to hear from you. Tell us about your adventures of diving and snorkeling, in the comments below. Please also share your photos. Either from your underwater cameras or videos from your waterproof Gopro’s!

If this article hasn’t answered all of your questions. If you have more questions either about snorkeling or scuba diving (or specifically about what is it called when a diver comes up too fast), please comment below with your questions.

There will also be many more articles about scuba diving (and snorkeling) for you to read and learn about these fabulous sports.

Have fun and be safe!